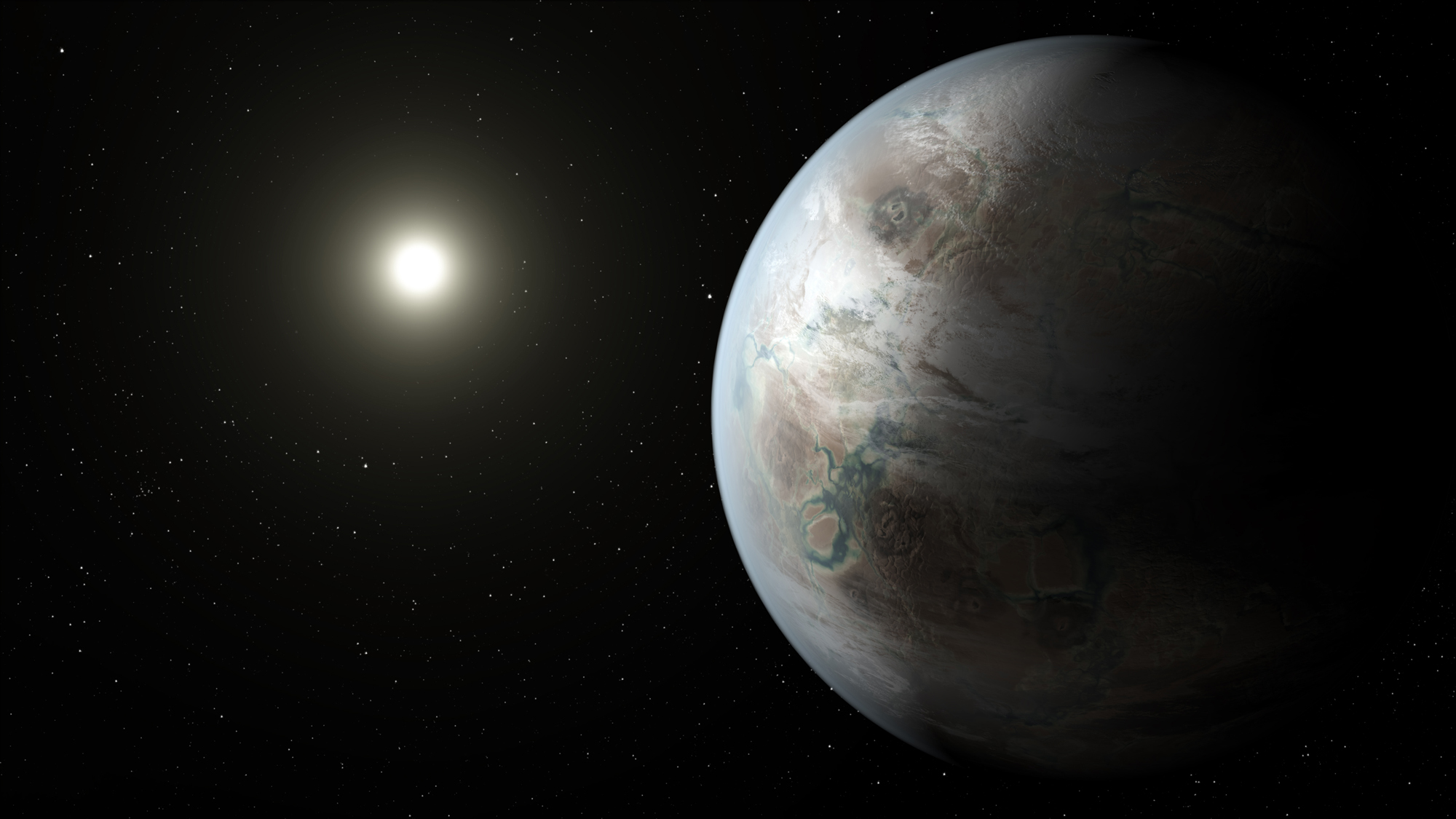

It may not be Earth's exact twin, but it's a pretty close cousin.

NASA's Kepler space telescope has spotted the most Earth-like alien planet yet discovered — a world called Kepler-452b that's just slightly bigger than our own and orbits a sunlike star at about the same distance Earth circles the sun.

"This is the first possibly rocky, habitable planet around a solar-type star," Jeff Coughlin, Kepler research scientist at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute in Mountain View, California, said during a news briefing today (July 23). [Exoplanet Kepler 452b: Closest Earth Twin in Pictures]

"We've gotten closer and closer to finding a true twin like the Earth," Coughlin added. "We haven't found it yet, but every step is important because it shows we're getting closer and closer. And this current planet, 452b, is really the closest yet."

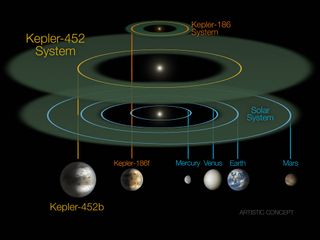

Scientists have discovered other small, potentially habitable exoplanets, but those previous finds orbited red dwarfs, stars much smaller and cooler than the sun.

Meet Kepler-452b, Earth's closest twin

![The mission of the Kepler Space Telescope is to identify and characterize Earth-size planets in the habitable zones of nearby stars. [See how NASA's planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft works in this Space.com infographic]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/Y5zsbomX7KxA8W6LjFsGU8-320-80.jpg)

Kepler-452b lies 1,400 light-years away, and is the only planet known in its solar system. It's about 60 percent wider than Earth, which gives it a "better than even" chance of being rocky, researchers said. The planet is probably about five times more massive than our own, making it a so-called "super Earth." It likely possesses a thick atmosphere, lots of water and active volcanoes.

The exoplanet completes one orbit every 385 days, so its year is only slightly longer than Earth's. And Kepler-452b circles a sunlike star that's just 10 percent bigger and 20 percent brighter than the one that hangs in Earth's sky.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It would feel a lot like home, from the standpoint of the sunshine that you would experience," said Jon Jenkins, Kepler data analysis lead at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. (Jenkins led the team that discovered Kepler-452b.)

But Kepler-452b's star appears to be considerably older than the sun — 6 billion years, compared to 4.5 billion years.

"It’s awe-inspiring to consider that this planet has spent 6 billion years in the habitable zone of its star; longer than Earth," Jenkins said in a statement, referring to that just-right range of distances that could support the existence of liquid water on a world's surface. "That’s substantial opportunity for life to arise, should all the necessary ingredients and conditions for life exist on this planet."

Kepler-452b's existence was announced with the release of the latest Kepler catalog, which includes 521 new planet "candidates" dug out of the data the spacecraft gathered during its first four years of operation. (Kepler, which launched in March 2009, stopped observing under its original planet-hunting mission in May 2013, after the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed.)

Eleven of the 521 newfound candidates are, like Kepler-452b, less than twice as wide as Earth and reside in their host stars' habitable zone, researchers said.

Kepler's total haul of potential exoplanets is now nearly 4,700. Just 1,030 of these finds have been confirmed to date, but mission scientists expect that the vast majority — 90 percent or so — will end up being the real deal, just like Kepler-452b.

During its original mission, Kepler stared at more than 150,000 stars simultaneously, looking for tiny brightness dips caused by planets crossing these stars' faces. Kepler's dataset is therefore huge, and it has taken researchers a while to analyze it and address the main goal of the $600 million mission — determining how common Earth-like planets are across the Milky Way galaxy.

Analyses of Kepler observations to date suggest that about 20 percent of the Milky Way's stars harbor at least one rocky planet in the habitable zone, but this number will be revised or refined with additional study, researchers said.

"Continued investigation of the other candidates in this catalog and one final run of the Kepler science pipeline will help us find the smallest and coolest planets," the SETI Institute's Joseph Twicken, lead scientific programmer for the Kepler mission, said in a different statement. "Doing so will allow us to better gauge the prevalence of habitable worlds."

Indeed, the team plans to release the eighth Kepler catalog next year. Continued software improvements and the knowledge gained during previous analyses of the dataset should lead to more exciting finds by the mission science team — and by researchers who study the publicly archived data in the future, Coughlin said.

"I really expect that discoveries will be coming from Kepler for the next several decades," he said.

Kepler: NASA's prolific planet hunter

But Kepler isn't done observing the heavens. In May 2014, NASA approved a new mission called K2, in which the spacecraft is studying a variety of cosmic objects and phenomena, including distant supernova explosions, comets and asteroids in our own solar system and exoplanets. And a compromised Kepler can indeed still spot alien worlds: NASA announced the K2 mission's first exoplanet find in December 2014.

The first exoplanet was spotted in 1992, and researchers have discovered nearly 2,000 confirmed alien worlds in the 23 years since then (the exact number varies depending on which database is consulted). The Kepler spacecraft is responsible for more than half of these finds.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.